Table of Contents

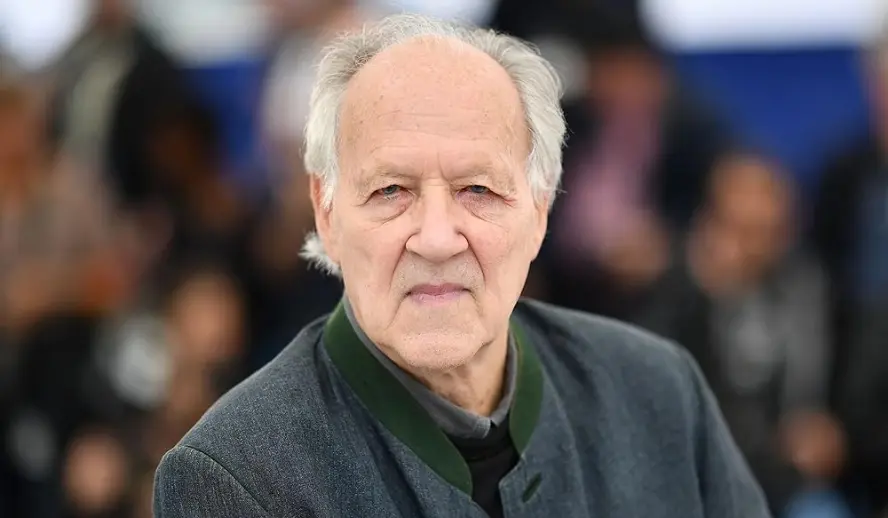

Werner Herzog: Champion of the Outsider

When I tell you that Werner Herzog once held an actor at gunpoint upon that actor’s refusal to act, you may wonder how he hasn’t been canceled (Herzog denies pulling the gun but not threatening his star’s life). When I tell you that the actor, Klaus Kinski, was considered a madman by his co-stars due to his erratic behavior, which included blindly firing a rifle through the side of a hut where the crew of the film ‘Aguirre, the Wrath of God’ (1972) were playing cards, you may wonder how Klaus Kinski was not canceled.

It’s a good thing that the average movie set isn’t inhabited by a collaboration as frightening as those between Herzog and Kinski, but the relationship between the two serves as a microcosm for the darkly compelling heart of many of Herzog’s films. Where others designated Kinski a madman, Herzog called him “a terrifying genius.” Herzog seeks out unusual, quixotic subjects wherever he can and centers them in his films without exploiting them.

Whether it be a documentary about the infamous Timothy Treadwell, who spent years documenting his interactions with wild bears (‘Grizzly Man,’ 2005), or a feature film about the mysterious foundling Kaspar Hauser (‘The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser,’ 1974), Herzog directs movies that leave observational room between us and the outsider protagonist, allowing them to square off against the natural world without intervention. Or at least, that is the tone and artistic effect.

Things to do:

- Subscribe to The Hollywood Insider’s YouTube Channel, by clicking here.

- Limited Time Offer – FREE Subscription to The Hollywood Insider

- Click here to read more on The Hollywood Insider’s vision, values and mission statement here – Media has the responsibility to better our world – The Hollywood Insider fully focuses on substance and meaningful entertainment, against gossip and scandal, by combining entertainment, education, and philanthropy.

Herzog’s Interjections

Werner Herzog infamously writes philosophical musings for his documentary subjects, arguing that a “poetic, ecstatic truth” can be revealed through cinema, deeper than factual truth. It can be a little jarring to learn that some of the most memorable lines in his documentaries are inorganic. I personally felt heartbroken to learn that Herzog dreamt of ski jumping as a child since that means there’s a good chance that Fini’s memory of ski jumpers in ‘Land of Silence and Darkness’ (1971) was fed to her. Herzog, in fact, filmed a documentary about a ski jumper three years later: ‘The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner’ (1974). Fini Straubinger, who lost her sight and hearing in adolescence, shares her perspectives on being deaf-blind in Herzog’s unforgettable documentary, and it’s hard to know which of her insights are unfiltered.

In the larger scope of Herzog’s vision for cinema, however, there’s something honest about how directly he injects his ideas into his movies. Herzog has gone to great lengths to depict how isolated each person can be from their own reality, and it would feel disingenuous to see a movie about personal reality presented as a reportage of indisputable fact. To take Fini as the ultimate authority on the experience of the deaf-blind, for example, would ignore the differences between her and Vladimir Kokol, the uneducated 22-year-old young man, deaf-blind from birth, whose lonely lip-trilling and self-hitting occupies an uninterrupted three and a half minutes of the film before Fini interacts with him.

There’s a series of scenes in ‘Little Dieter Needs To Fly’ (1997) that I feel encapsulates this clash between fact and the auteur’s vision. Dieter Dengler, an escaped POW of the Viet Cong, recounts the details of his imprisonment and escape, and Herzog recruits local Laotians to dress as the Viet Cong and stand around Dengler as he tells the story. There’s a strange effect produced by the contrast between Dengler’s animated retelling and the Laotian actors’ indifference. We are brought closer to Dieter’s experience, but reminded that he alone lived it and we are about as close to understanding it as the people making up the tableaux behind him. Herzog’s decision to create an obviously staged image rather than enlist actors to fully reenact the events of Dengler’s life allows us to see Dengler as he is now–a complicated, oddly cheerful man living with unbelievable trauma. It focuses on him instead of one sensational chapter in his life. Strange as it is to watch, it stirs the subconscious in a way that most documentary interviews don’t.

Herzog would return to this subject when he directed ‘Rescue Dawn’ (2006), a feature film about Dengler’s imprisonment and escape starring Christian Bale, and despite being a powerful escape/war movie with Herzog’s absurdist touch, it’s not as powerful as the documentary.

WATCH THE TRAILER of the Film and the Revolution: ‘Can I Go Home Now?’

The Children Around the World Continue to Ask the question

The Cinematic Ends of the Earth: Romantic or Colonial?

Faced with a torrent of new movies and TV shows, many of them beholden to franchise guidelines or target audiences, it can be easy to forget the most basic pleasure Cinema can afford: seeing something new. When so much of our media is formulaic, even movies we’ve never seen before feel familiar and their imagery forgettable.

With Werner Herzog’s movies, you will almost always see footage that you haven’t seen anywhere else. Whether it be the vast, burning oil fields in ‘Lessons of Darkness’ (1992), or the entirety of ‘Cave of Forgotten Dreams’ (2010), which captures on film the oldest preserved paintings in human history, you see something you’ve likely only heard about before.

At the end of ‘Aguirre, the Wrath of God,’ for example, Don Lope de Aguirre (Klaus Kinski) stands on a raft in the Amazon River, eyes fixed on the sky. Around him, the members of his exploring party have been stricken dead by arrows and spears, and a few dozen monkeys forage for what food remains. On another trip (5 years long, so more like relocation) to the Amazon, Herzog filmed his most notorious work: ‘Fitzcarraldo’ (1982). Based on the true story of an Irish entrepreneur who tried to build an opera house in the middle of the Amazon rainforest, in Herzog’s hands, it becomes an epic call for the hauling of a steamboat over a mountain. The extensive list of injuries and even deaths that occurred while filming ‘Fitzcarraldo’ has caused controversy about the ethics of making it, but what is undeniably true is that no other movie is like it. Should you take on the two-and-a-half-hour film, you will see hundreds of people level a mountain and drag a steamboat over it, for real.

Herzog’s questionable treatment of indigenous people should not go unmentioned. Debates circle around the production of ‘Fitzcarraldo’ about whether the rate of injury and death exceeded what would normally take place across five years in the Amazon. The barracks-style housing provided for the Amahuaca people who performed much of the labor needed to pull off the movie’s conceit, on the other hand, too closely resembled a labor camp for modern audiences to give the movie unbridled praise in the way that many critics did after the film’s original release. And the conceit itself–achievement of the impossible at the expense of one’s safety and the safety of those around oneself–does not fit unproblematically into a film about an Irishman trying to culturally educate natives of the jungle.

The uniqueness of Herzog’s imagery is not limited to the dubiously grandiose, however. Herzog, like many of his New German Cinema contemporaries, lets the camera linger, allowing the minutiae of life to take up screen time. He often includes a mixture of the grandiose and minute in exciting ways.

Related article: – Want GUARANTEED SUCCESS? Remove these ten words from your vocabulary| Transform your life INSTANTLY

Related article: From Bob Dylan to Beyoncé, These Are The Most Memorable Music Documentaries

The Greatest Treasure: Bruno S

Two of Herzog’s greatest films, ‘The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser’ and ‘Stroszek’ (1977), share in common the best actor he ever hired, and that includes Christian Bale. No outcast fits more brilliantly into a Herzog story than Bruno S., not even Klaus Kinski. Bruno S. was a genuinely odd person with dreams bigger than himself, which is exactly the kind of subject Herzog loves to pit against the overwhelming world. Unlike Kinski, Bruno S. bears with him an incredible sensitivity that makes him easy to root for and sympathize with, even at his strangest.

In ‘The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser,’ Bruno plays the mysterious German foundling, Kaspar Hauser. Hauser is socialized over time after being released from isolation in late adolescence. Hauser has visions that metaphorize the human condition, all of them involving aimlessness in some vast, engulfing environment, particularly the one on his deathbed of a desert caravan being led by a blind man. Herzog captures these visions on film, and the result is a profound surreality contrasted against Hauser’s base origins. “It seems to me that my coming into this world was a very hard fall,” Hauser says to one of his patrons, and Herzog would have us believe that no amount of procedure and formalization can lift us too far from that hard fall. Hauser’s pristine metaphors his clarified views of the world, come from his realization that he is base, and through Hauser, the audience too can see how we deceive ourselves into thinking we are far from Hauser’s existence.

In ‘Stroszek,’ Bruno plays a Berlin busker who emigrates to America with a prostitute and his neighbor, only to find himself more destitute and alone than before. The film takes wonderful, meandering turns as confused as Stroszek himself. Stroszek eventually succumbs to despair in the final scene: one of the most sustained frenzies in all of film, and another instance of Herzog highlighting the chaos that awaits us just beyond our controlled reality. The film was written specifically for Bruno, even using his home as Stroszek’s home in the film.

On their own merit, these are two of Herzog’s best films, featuring footage both dreamlike and nightmarish, following their subjects wherever they lead, and with a subject like Bruno S, that place is always worth going to. I say this quite possibly to the chagrin of many Herzog fans, but I recommend starting with the Bruno S movies and then finishing with them. Bruno S captures the best of Herzog’s ambitions as a filmmaker, and the movies featuring him shed light on the rest of Herzog’s filmography.

Speaking of which, some other notable titles that portray what I’ve pondered in this article include: ‘Cobra Verde’ (1987), ‘The White Diamond’ (2004), ‘Into the Abyss’ (2011), and his more recent ‘Family Romance, LLC’ (2019). Like Herzog’s journey as a filmmaker, each of these films is a quest unto itself.

By Kevin Hauger

Click here to read The Hollywood Insider’s CEO Pritan Ambroase’s love letter to Cinema, TV and Media. An excerpt from the love letter: The Hollywood Insider’s CEO/editor-in-chief Pritan Ambroase affirms, “We have the space and time for all your stories, no matter who/what/where you are. Media/Cinema/TV have a responsibility to better the world and The Hollywood Insider will continue to do so. Talent, diversity and authenticity matter in Cinema/TV, media and storytelling. In fact, I reckon that we should announce “talent-diversity-authenticity-storytelling-Cinema-Oscars-Academy-Awards” as synonyms of each other. We show respect to talent and stories regardless of their skin color, race, gender, sexuality, religion, nationality, etc., thus allowing authenticity into this system just by something as simple as accepting and showing respect to the human species’ factual diversity. We become greater just by respecting and appreciating talent in all its shapes, sizes, and forms. Award winners, which includes nominees, must be chosen on the greatness of their talent ALONE.

I am sure I am speaking for a multitude of Cinema lovers all over the world when I speak of the following sentiments that this medium of art has blessed me with. Cinema taught me about our world, at times in English and at times through the beautiful one-inch bar of subtitles. I learned from the stories in the global movies that we are all alike across all borders. Remember that one of the best symbols of many great civilizations and their prosperity has been the art they have left behind. This art can be in the form of paintings, sculptures, architecture, writings, inventions, etc. For our modern society, Cinema happens to be one of them. Cinema is more than just a form of entertainment, it is an integral part of society. I love the world uniting, be it for Cinema, TV, media, art, fashion, sport, etc. Please keep this going full speed.”

More Interesting Stories From The Hollywood Insider

– Want GUARANTEED SUCCESS? Remove these ten words from your vocabulary| Transform your life INSTANTLY

– A Tribute to Martin Scorsese: A Complete Analysis of the Life and Career of the Man Who Lives and Breathes Cinema

– Do you know the hidden messages in ‘Call Me By Your Name’? Find out behind the scenes facts in the full commentary and In-depth analysis of the cinematic masterpiece

– A Tribute To The Academy Awards: All Best Actor/Actress Speeches From The Beginning Of Oscars 1929-2019 | From Rami Malek, Leonardo DiCaprio To Denzel Washington, Halle Berry & Beyond | From Olivia Colman, Meryl Streep To Bette Davis & Beyond

– In the 32nd Year Of His Career, Keanu Reeves’ Face Continues To Reign After Launching Movies Earning Over $4.3 Billion In Total – “John Wick”, “Toy Story 4”, “Matrix”, And Many More